Note: This is a piece that may be quite useful if you're a personal finance novice (like myself) and a waste of time if you're even moderately well-versed in the topic. If you're already well-versed, then please feel free to stop right here.

Recently over dinner a friend gave me one of the most actionable pieces of personal finance advice I've heard: "Taxes compound too." Like many great pieces of advice, it seemed so obvious in retrospect that I felt dumb for not having thought about it already.

What did he mean by that? We've all heard some variant of "interest compounds" - if you invest in an asset that returns a certain percentage a year, or accrue interest, it'll exponentially grow. 10% a year becomes 21% returns after 2 years and 159% return after 10 years. But the same applies to taxes, just in the opposite direction.

As quick background, investment gains are typically taxed at a rate depending on income and duration of how long you held the investment (short term vs. long term). This means that upon selling an asset, you are taxed a certain percentage of the difference between what you bought an asset for and what you sold it for.

Now consider a simple contrived example:

- You have $100 and can invest it in some stocks that give 100% annual returns (that is, it doubles in value every year).

- You get taxed at 50% of capital gains. Every time you sell your stocks you pay 50% of how much gain your investment accrued to Uncle Sam

Now consider 2 investment strategies (resulting $ amount in parentheses):

Strategy 1:

- Invest $100 for 2 years ($100 —> $100 x 2 x 2 = $400 in stocks)

- Sell it and retire ($400 in stocks —> $400 - 50% x ($400 - $100) = $250)

Strategy 2:

- Invest $100 for 1 year ($100 —> $100 x 2 = $200 in stocks)

- Sell it ($200 in stocks —> $200 - 50% x ($200 - $100) = $150)

- Reinvest for 1 year ($150 —> $150 x 2 = $300 in stocks)

- Sell it and retire ($300 in stocks —> $300 - 50% x ($300 - $150) = $225)

The act of selling your investments just one more time, and thus getting taxed one extra time, makes you end up with with $25 or 10% less in this example.

This compounds very quickly if you do this multiple times, hence "taxes compound too." Sparing the math, in this same contrived example if you have a 10 year investment horizon and choose to sell (and get taxed) only when you retire you end up with $51,520. Versus if you're selling (and getting taxed) and reinvesting every year, you end up with $5,766.50, almost 10 times less.

The important intuition is that selling your assets and consequently getting taxed is a negative interest move. Positive interest compounds but so does negative interest, in a way that's bad for you.

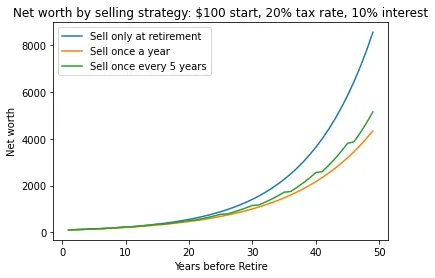

These numbers aren't super realistic so let's take much more realistic numbers. Let's take a capital gains tax rate of 20%, and an annual return on stocks of 10%. Assuming $100 invested on day 1, here is a comparison of:

- only selling at retirement

- selling every year and reinvesting

- selling every 5 years and reinvesting

Assuming an average work career length of 40 years, you're giving up ~40% of your upfront investment if you're selling it, getting taxed on that, and reinvesting every year. If you're only doing it every 5 years, you're giving up 30%.

What does this mean for what to do in practice?

- Max out your non-(withdrawal) taxable accounts like your Roth IRA. In these accounts you can sell without biting the 20% tax rate each time.

- On capital gains taxable accounts, one should err on the side of always holding rather than selling investments that appreciate in value. Every time additional time you sell your investment, you are compounding the taxable percentage, e.g. "negative interest rate", on your overall portfolio

- Be particularly wary of short term capital gains, that is selling within a year of buying an asset, where the tax rate is even higher than if you hold for 1 year+

One may argue that most people sell an asset expecting to be able to reinvest in a higher interest bearing asset. However to break even you would need 12% returns, or the capital gains tax rate of 20% higher than the original asset. This 12% - 10% = 2% difference sounds small, but is extraordinarily difficult to achieve over the long-term1.

There are also valid diversification related concerns, e.g. if certain assets have become too large a percentage of your portfolio then perhaps it makes sense to diversify the risk across multiple assets. I'm unable to give a universal answer to this as the benefits of diversification depend strongly on ones utility curve as a function of possible net worth outcomes. However, I'd err on the side of taking the higher expected value over the lower risk option as a young individual, particularly when it has compounding consequences when repeated. If you do wish to sell gains to rebalance, it'd be wise to do so as infrequently as possible.

- Note that I believe it is possible to 'beat the market', I just think it’s very unlikely that the average retail investor is able to do so by expectation (though of course it is possible year to year due to variance).↩