Introduction

There are 2 ways to win a basketball game: get more scoring attempts off ("possession") or score more points per scoring attempt ("efficiency"). As shooting efficiency becomes comparatively more of a solved problem in the league,1 I've become fascinated by the possession game, and its interaction with efficiency. This piece explores one aspect of the possession game: crashing the offensive glass.

Traditional wisdom is that on balance, crashing for offensive rebounds is net bad because of the costs it incurs on transition defense2, although this philosophy is evolving to some extent as well3. This is hard to prove with a high degree of confidence in either direction with publicly available data because on a play by play basis, we can only see the result of whether there was an offensive or defensive rebound, not whether there was a crash attempt (and from whom) itself.

At a higher level, it's hard to define what crashing for a rebound even means - is any movement towards the basket "crashing" on an individual level? What if you're already in the vicinity of the basket? How many people must crash to constitute a team "crash"? Moreover, even trying to use proxy variables like the result of a rebound attempt in order to prove causality is tough because of certain selection effects: teams who are bad at shooting tend to crash more, teams crash more when they're down, etc. To go from "teams who crash more are better/worse" to "crashing causes teams to be better/worse" requires proof of causality.

What I have more confidence in is that situationally crashing can be a good idea and we need to carefully consider the opportunity costs. This piece is a bit of a hodgepodge of hypotheses around crashing. The unifying theme, to the extent that there is one, is that optimizing crashing and the offensive rebound game requires navigating a series of tradeoffs, notably with first-shot offense and transition defense. There may be situations where the tradeoff can be avoided or even flipped.

(Simplified) Anatomy of a Crash

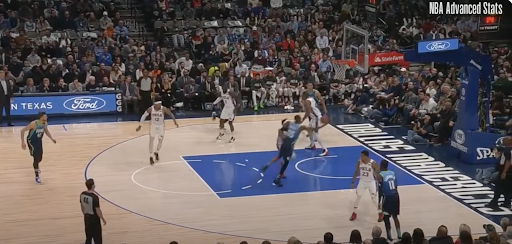

To begin, lets outline what a crash looks like along various decision points. Consider this play that develops into offensive rebound by Dorian Finney-Smith:

We can split a crash opportunity like this into at least 4 steps:

- Pre-Shot Positioning

From left to right of the ball, Finney-Smith is in the weakside corner, Powell is in the dunker spot, Kleber is on the wing, and Hardaway Jr. is on the strongside corner. As we'll delve into, this has effects on all of first shot offense, crash probability, and the chance of securing a rebound.

- The Shot

The shooter Wright attempts a driving layup in the paint in isolation against Richardson. Note that details of the shot such as degree of help drawn and location4 has a large impact on the potential rebound outcome.

- The Decision to Crash

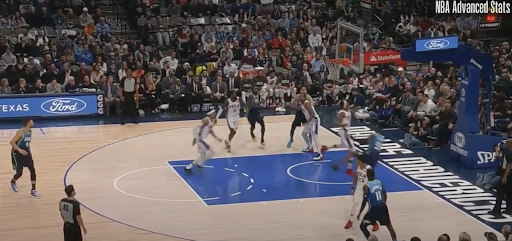

As the shot is going up, Finney-Smith and Powell crash to the basket, while Kleber and Hardaway Jr. (as clear from the bottom image) begin to retreat. Finney-Smith takes a "backdoor" crash path to the basket from the corner while Powell is more stationary because he's being boxed out by Horford.

- 4A. (Conditional on an Offensive Rebound) 2nd Chance Offense

Finney-Smith gets an immediate putback layup out off the offensive rebound. Note that these putback opportunities are often easier than the original shot attempt because the defense is often out of position on the ensuing rebound scram. If the second chance offense has to reset this edge is no longer as prominent, particularly with the shotclock reset now being 14 seconds instead of 24 seconds.

- 4B. (Conditional on a Defensive Rebound) Transition Defense

Because this ends up in a made second chance shot, transition defense is not a factor. However, if the shot had missed, the personnel as well as some of the strategic decisions made in steps 1-3 would have had a significant effect on the transition defense. For example, one could argue that Dallas' floor balance is off, with 4 players past the free throw line extended, allowing Philly the easy possibility of leaking out in transition conditional on securing the defneisve rebound. On the other hand, all 5 Philadelphia players have also committed to being inside of their own free throw line extended, with several attempting to provide defensive rebound support, meaning there's no one to outlet to.

Space and Crash

One of the key contributors to the interaction effects between offensive rebounding and shooting efficiency is pre-shot positioning ("Step 1"). Widely scheme and personnel dependent, but positioning forwards outside the 3-point line generally improves first-shot offense (by giving the initiator more space to operate) but generally decreases offensive rebounding chances (by increasing the distance from a potential offensive rebounder to the basket; as we'll discuss later on in this section though, spacing out the opposing best defensive rebounders may provide large advantages). In 2016, Zach Lowe5 noted:

The historic drop-off goes beyond transition paranoia. Teams are playing more small ball, and asking their power forwards to shoot 3s -- slotting good rebounders 25 feet from the rim. "You're just so far away," says Kris Humphries, who barely snags offensive boards now that the Wizards have turned him into a 3-point shooter. "It's hard to run all the way in, and then run back on defense." Kevin Love, Serge Ibaka, Scola and lots of other reinvented snipers could empathize.

In 2023, we can replace "power forwards" to "forwards and centers" and "25 feet" to "30 feet" and the quote would still be accurate: teams have gone from 4-out to 5-out offenses at a much higher rate and spotting up deep behind the 3-point line has become common.

Given the (warranted) focus on space in modern offenses, I believe players who can space and crash from the 3-point line on the same possession will become very valuable. Broadly speaking, there are 2 semi-overlapping categories of offensive rebound crashes:

- a player (often a big) is already near the basket and in position to get the rebound (call it "static crashes")

- a player (often a wing) crashes in from the perimeter, often the corner 3 or sometimes the wing 3, to collect the rebound ("dynamic crashes")

Those who can credibly spot up, thus not hurting first-shot spacing, and dynamically crash, thus improving the odds of a second chance, on the same possession will likely have outsized value compared to players who force a tradeoff between spacing and offensive rebounding. The Finney-Smith clip above is one such example, as well as several from Kawhi's insane 2019 postseason run. The corner may be more feasible to crash from given the shorter distance to the basket, but crashing from above the break is also possible for special athletes like Kawhi.

Even for players without the most credible 3-point shot, crashing from the perimeter may be a way to punish defenders that are completely sagging off. Consider this play from the end of the Knicks-Cavs 2023 Game 1 that nearly broke the New York sports bar I was watching the game in:

Note that Mobley's boxout on Randle comes late because he's not closely guarding Randle on the perimeter and instead choosing to hone in on Brunson and the ball. As a result, Randle is able to crash in from above the break and secure the game-winning offensive rebound.

Drive and Kick and Crash

Another situation to gain an offensive rebounding edge while maintaining spacing and avoiding transition defense leakage is having the initiator stay near the basket in rebounding position on kickouts. Consider this play from Lauri Markkanen:

Plays like this where the creator stays near the basket to offensive rebound after driving can be very valuable because at that point they don't have a clear boxout matchup especially if they've drawn help. For a bigger creator like Markannen this can be a deadly way to generate extra putback opportunities.

Further, Markannen isn't harming first-shot spacing because he's the ones using the space created and has already created a good look at 3, and as the initiator with forward momentum he likely wouldn't have been in position to retreat back on defense anyway.

This clip also illustrates the importance of spacing for rebounding purposes. Atlanta's best defensive rebounder in Clint Capela is dragged out to contest the 3-point shot from Olynyk, leaving Markkanen with a relatively uncontested look at a tip-in.

Game State

When a team is behind especially later in a game, crashing for offensive rebounds becomes more valuable because the opportunity cost of giving up transition defense is lower. This is because the team is in a position where they need to score more points and should be risk-seeking; in the limit at the very end of the game, if they score they have a chance to win the game, if they don't they had no chance to win anyways, so giving up a transition bucket doesn't change their win probability. In addition, the opposing team is less likely to push in transition because of clock management reasons so the tradeoff is even less dangerous.

This also holds for end of quarter situations. In situations where there's not enough time for the other team to get a bucket off, it's clear that crashing aggressively has no tradeoffs to transition defense. In situations where there is enough time for the other team to get a bucket off, the other team will likely want to take the last shot so will be less likely to push in transition anyways. If they do push in transition and score too quickly, your team now has the opportunity to get another shot off.

Another area that could require further exploration is crashing more in bonus situation. It is hard to track via public data but my intuition is that the increased chance of free throws from non-shooting fouls (for example when being grabbed to prevent an offensive rebound) adds a substantial amount of value to crashing when in the bonus.

Targeting

Attacking weak point of attack defenders is a widespread strategy in the league now, but attacking rebounding mismatches may be less prioritized despite trends in the league possibly making it more valuable.

The increase of spaced 5-out offenses makes relative rebounding ability (between an offensive player and his defender) comparatively more valuable than absolute rebounding ability. The reason is that if it's less likely that there's a primary rebounder camped out in the paint due to the effects of space, an offensive player may just need to beat his primary box-out to secure a rebound; this is the basis for the "dynamic crash" category of offensive rebounding discused earlier.

This is accentuated by the strategies of modern defenses. As defenses have gotten more switch-heavy, it's more likely that after a 2-man action, a smaller guard is the primary box-out defender on a big or a larger wing. This is a mismatch that can be exploited by the offense by having the big crash. By default, teams are also trying to hide their weakest defenders on players with less on-ball offensive ability. Due to selection effects, these players are often quite athletic, else they wouldn't have made it in the league without as much on-ball ability. A natural way to attack this mismatch that's situationally more effective than attacking them with the ball is to do so on the offensive glass.

Crashing the glass against teams and players who do not push in transition at a high rate may be a component of a targeting strategy. Certain initiators known to prefer half-court offense may be better targets for crashing than those who may punish a failed crash attempt with consistent push-ahead play. On the other end of the court, against players who do not crash at a high enough rate there is likely a strategic advantage to be had having their defenders leak out early in transition when the shot goes up.

Further Questions

Thanks for getting to the end of this brain dump. Some further questions I have include:

- Which players are generating large offensive rebounding value when they do crash but don't crash at a high rate? And vice versa?

- Is this due to coaching or is it due to a lack of motor or some other individual issue?

- Is positioning and decision-making over when to crash an individual skill or something comparatively more coachable?

- To be clear it is nowhere close to completely "solved." But if you look at simple heuristics like 3PA rate, the rate of increase is slowing down, and there seems to be a general understanding that 3's, rim shots, and free throws are the most efficient shots. Getting to those shots is a different question though.↩

- https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/14505051/transition-defense-left-offensive-rebounds-cutting-room-floor↩

- https://www.thescore.com/nba/news/2536613↩

- https://squared2020.com/2019/11/18/offensive-crashing/↩

- https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/14505051/transition-defense-left-offensive-rebounds-cutting-room-floor↩