This has been removed for the time being as I may work on some of these ideas with a basketball team. Please contact me if you'd like to discuss further.

3 posts tagged with "basketball"

View All TagsExotic Picks

“The only thing to bridge the gap [in player value] is draft picks and to me, they’re like cigarettes in prison... That’s the only currency you have. The value changes up and down all the time and it makes for a not very liquid market."

This quote from the 2018 Sloan Conference1 illustrates a key problem with draft picks as a means of exchange: they are illiquid.

This interested me given in theory a draft asset can be valued anywhere from near nothing (e.g. a top-55 protected 2nd round swap) to highly valuable (e.g. several unprotected first round pick from a team projected to be one of the worst in the league), and almost everywhere in between.

This piece is an exploration of creative ways to structure deals involving draft picks to make them more liquid; that is, filling in the "everything in between" studio space a bit more. The inspiration for the title is the arbitrarily complex set of derivative financial assets that financial engineers have created, called Exotic Derivatives, to fuel the Wall Street casino. It is a work in progress.

The Constraints

According to the CBA Bible2, the following constraints (non-exhaustive, ignores the matching salary and player components) must be satisfied in any draft pick trades:

- "Seven Year Rule" - draft picks more than 7 years in the future can't be traded.

- No more than 55 picks in a single draft can be protected.

- "Stepien Rule" - A team may not trade away all first round draft picks in consecutive years. However, they may trade away their own (or another team's) so long as they are in possession of at least 1 unprotected draft pick in that window.

- Teams can add protections to picks it acquires only if they received the pick in an unprotected form.

- One-time options to defer the conveyance of a pick for 1 year can be added to unprotected picks.

These rule-based constraints along with several practical constraints surrounding team-building make draft pick trades that are both mutually palatable and allowable for all parties tough to come by. What follows is a description issues that get in the way of deal-making and and potential creative alternatives, from relatively tame to wacky. We will use the logic from Programmatic Draft Valuation to approximate the value of draft assets.

(As a caveat I'm not sure if all of these are all legal with certainty, just that if they were they would be interesting.)

Creative Pick Concepts

Specific Pick Protections on Swaps

The Stepien Rule applies to any chance that a team won't have a first-round picks in consecutive years. This means that the downside to constructs like multi-year pick protections is that they hamper the ability for a team to trade picks in any subsequent year surrounding the years to which the protections apply.

It is well-known that swaps are a way to get around the Stepien Rule issue. A lot of the trades involving multiple swaps are specifically designed to get around the Stepien Rule for teams that have traded out all their first round picks, for example Phoenix trading swaps for Beal after giving up most of their tradeable draft picks for KD. Even when it's not born out of necessity though, swaps can be a way to increase the liquidity of draft picks.

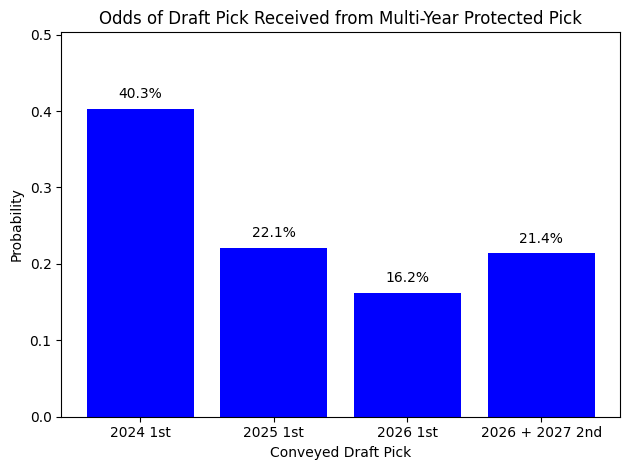

For example, consider the Kings draft asset that they sent Atlanta in the Kevin Huerter deal: protected 1-14 in 2024, 1-12 in 2025, 1-10 in 2026, and 2026 + 2027 2nds if not conveyed by then. Our basic model estimates that at the time of the trade, with the Kings coming off a season finishing 24th in the standings, using Pelton's 9-year surplus estimates, this asset is worth roughly 20.8 units (20.8% as valuable as the #1 overall pick). Here is the probability distribution of the various conveyances:

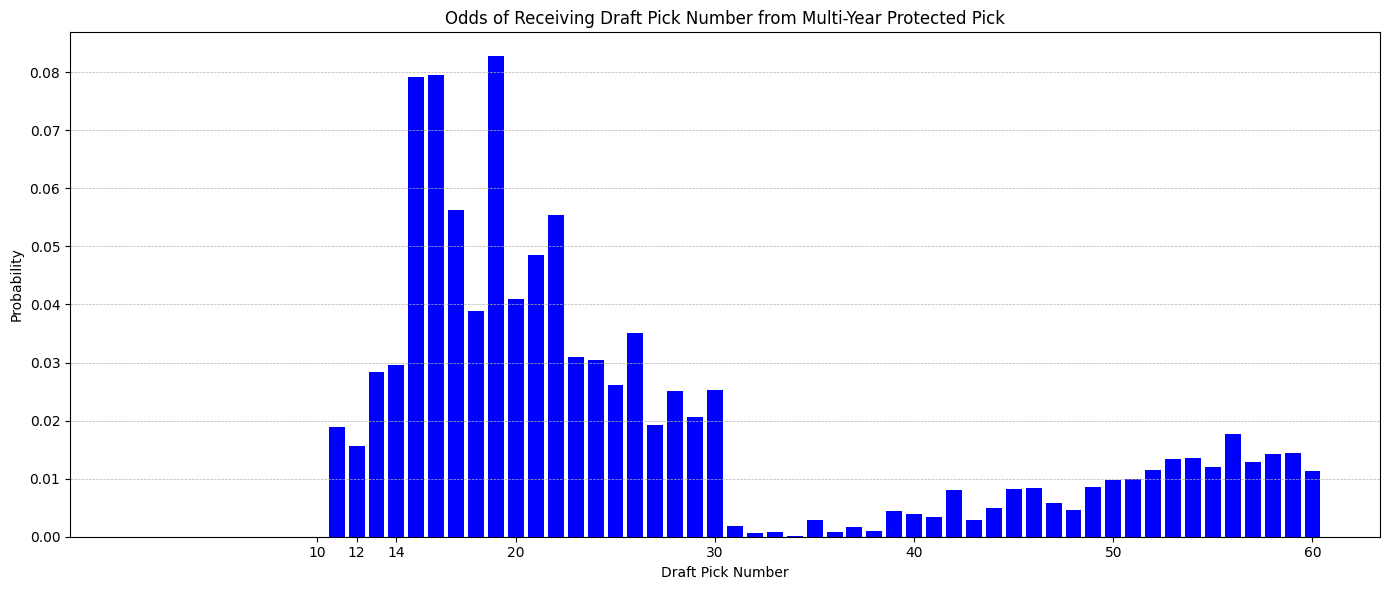

And what the distribution of picks this will end up being looks like:

However, this trade effectively prevents the Kings from trading any first round pick from 2023 to 2027 to avoid breaking the Stepien Rule, even if it is unlikely to last till 2027.

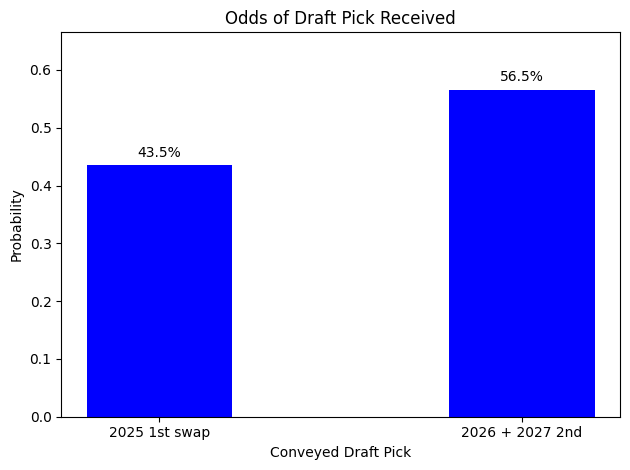

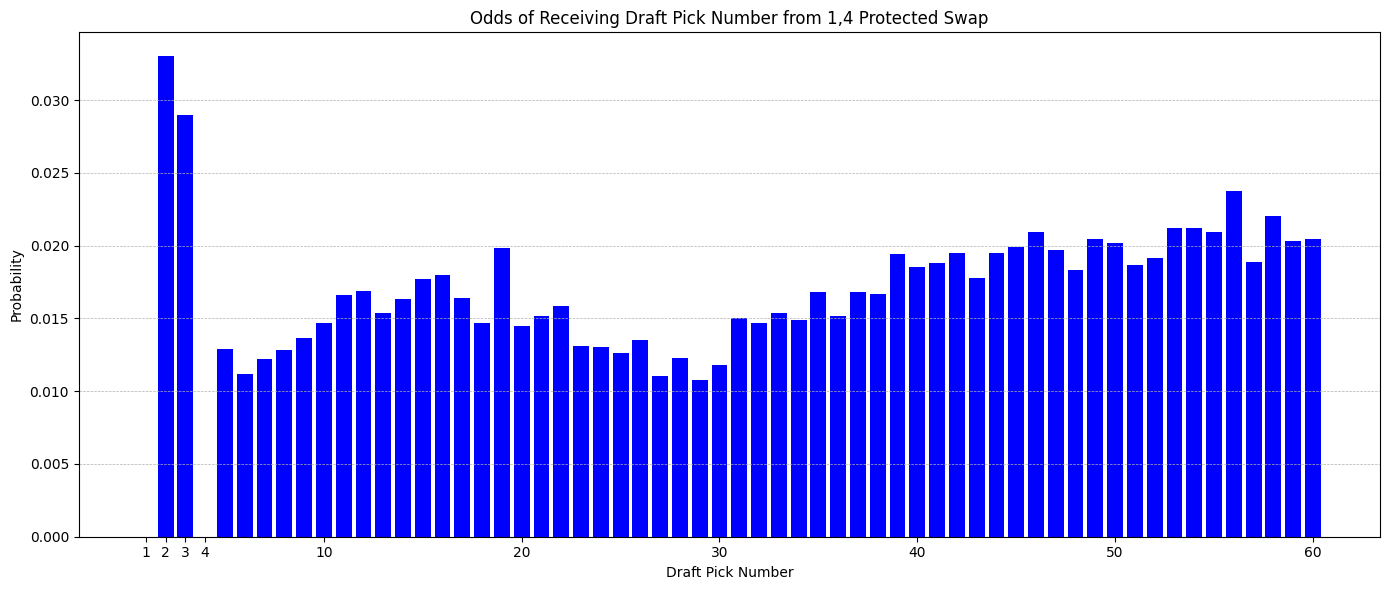

Instead, we can replicate the exact same expected value payoff with a 2024 right to swap that is protected for picks 1 and 4 (but not 2 and 3) turning into the 2026 and 2027 2nds if not conveyed, which comes out to worth exactly 20.8 in utility as well while maintaining the flexibility to trade any first round picks in the 2023-2027 window.

Note that odds of converting the 2nd or 3rd overall pick is elevated relative to the other draft picks, because if the Kings do land one of those picks they are almost certainly going to swap it with Atlanta, but a lot of the time end up just sending over a second round pick or a late first instead. This is a feature, not a bug.

There is nothing forcing us to protect within a continuous range: we can protect specific picks. In particular for picks 1-4, because every team in the lottery has a specified percentage chance of landing one of those picks, thinking carefully about which of them to protect can allow us to more accurately replicate the desired payoff.

Specific pick protections can also take advantage of a rare win-win scenario: a focused rebuilding team like OKC may have too many young prospects to roster, forcing them to make difficult roster crunch decisions and aggressively bundle picks to trade up in the draft, while a contending team trading them the pick likely doesn't want to tie up their draft pick flexibility for too many years into the future. Instead of receiving a multi-year protected pick, OKC can opt to receive the pick say if and only if it lands at pick number 2 or 3. This significantly reduces the probability they have to add another young prospect, but conditional on conveying, it is likely to be a very good one that they'd be more than happy to open up a roster spot for.

Further, we can use different draft pick values depending on the objective of the franchise - a team with a long time-horizon might opt for Pelton's 9-year surplus approach, a team that is more focused on the near-term might opt for a 3 or 4-year surplus approach, and a team that only values future championship odds might optimize for All-NBA probability.

Using Draft Protections Predictively

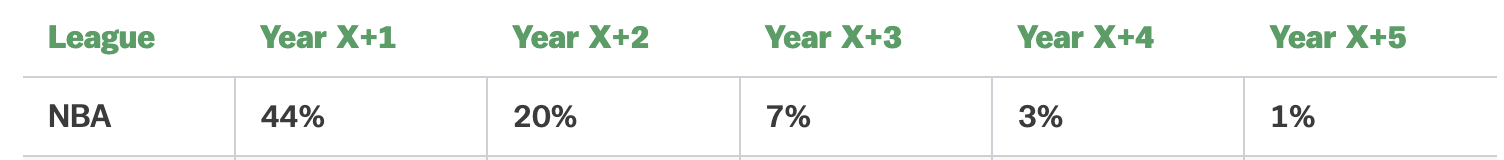

Standings and draft pick numbers by extension are fairly predictive one year out but not predictive more than a few years out4.

An aggressive team can use this predictive power, and lack thereof, to their advantage.

Suppose a team has agreed to send over an unprotected first round pick several years out. As a recipient team we want receive that pick in a year where the team is likely to be bad, but we have very little ability to predict which year that would be the case. If right now is 2023, we know very little about what the distribution of a team's 2026 pick will look like. But the 2026 pick tells us a lot about about what 2027 will look like.

A draft asset structured as follows could be interesting:

- 2026 1st: conveys if it's exactly pick number 15

- If it lands 1-14, turns into 2027 unprotected 1st

- If it lands 16-30, turns into 2030 unprotected 1st

The 2026 1st is essentially a dummy asset with almost no chance of conveying because it needs to be exactly pick 15. But what it does tell us is that we want next year's draft asset if it's a lottery pick, because that means the team is likely to be bad next year as well. If it's not a lottery pick, we want the pick 4 years out, because that means the team is likely to be good next year as well, while 4 years out we revert to base rates.

This is a creative (unsure if legal?) way to maximize the odds that the unprotected pick we receive comes at a time when the team is more likely to be bad, and hence land a high draft pick.

Protect Early, Swap Middle, Send Late (PSS)

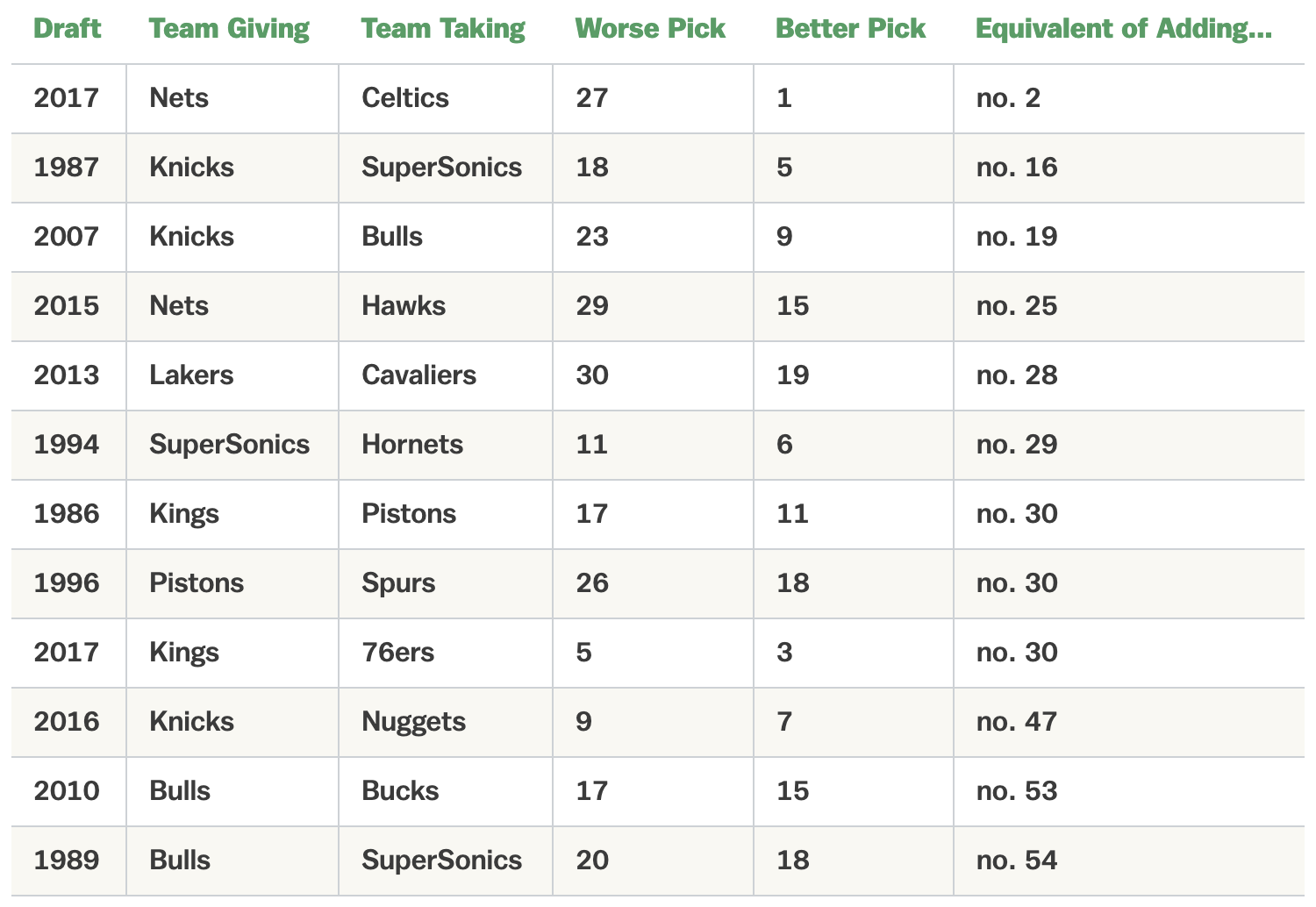

One issue with draft swaps is they often involve a contending team giving a rebuilding team the right to swap, which either becomes non-exercisable or less valuable if both teams mean revert to similar standings. For example, Zach Kram3 found that only 3 of 31 times, a swap gave a team the equivalent of a top-20 pick or better in value delta:

There are a few challenges to creating a mutually palatable swap deal:

- A team giving up a swap wants to be protected in the event that they receive one of the top picks.

- Swaps of mid to late draft picks have very little value.

- A recipient team probabilistically isn't going to be able to exercise a swap if they're bad.

One way to thread the needle here is the Protect Early, Swap Middle, Send Late (PSS) construction: protected 1-4, turns into a swap from 5-15, and is sent as a straight up pick if 15-30.

We can think of this as reverse protecting the delta of a swap. Even if the recipient team ends up being able to swap with a late pick, this swap will be worth very little, so receiving the pick outright ensures they're getting non-negligible value. Swaps become interesting if say a team can move up from the 20's to a pick in the 5-15 range. But protecting the 1-4 range ensures that the team giving up the swap is protected from the downside of the swap.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jL2ZSMQOOS4&t=431s↩

- http://www.cbafaq.com/salarycap.htm#Q89. Please let me know if any other constraints are missing; "Unlike most aspects of basketball operations, most specific trade rules are not found in the league’s collective bargaining agreement"3↩

- https://www.theringer.com/nba/2019/6/27/18760309/nba-title-windows↩

- https://www.theringer.com/nba/2022/10/12/23399637/nba-draft-swap-picks↩

Thoughts on Crashing

Introduction

There are 2 ways to win a basketball game: get more scoring attempts off ("possession") or score more points per scoring attempt ("efficiency"). As shooting efficiency becomes comparatively more of a solved problem in the league,1 I've become fascinated by the possession game, and its interaction with efficiency. This piece explores one aspect of the possession game: crashing the offensive glass.

Traditional wisdom is that on balance, crashing for offensive rebounds is net bad because of the costs it incurs on transition defense2, although this philosophy is evolving to some extent as well3. This is hard to prove with a high degree of confidence in either direction with publicly available data because on a play by play basis, we can only see the result of whether there was an offensive or defensive rebound, not whether there was a crash attempt (and from whom) itself.

At a higher level, it's hard to define what crashing for a rebound even means - is any movement towards the basket "crashing" on an individual level? What if you're already in the vicinity of the basket? How many people must crash to constitute a team "crash"? Moreover, even trying to use proxy variables like the result of a rebound attempt in order to prove causality is tough because of certain selection effects: teams who are bad at shooting tend to crash more, teams crash more when they're down, etc. To go from "teams who crash more are better/worse" to "crashing causes teams to be better/worse" requires proof of causality.

What I have more confidence in is that situationally crashing can be a good idea and we need to carefully consider the opportunity costs. This piece is a bit of a hodgepodge of hypotheses around crashing. The unifying theme, to the extent that there is one, is that optimizing crashing and the offensive rebound game requires navigating a series of tradeoffs, notably with first-shot offense and transition defense. There may be situations where the tradeoff can be avoided or even flipped.

(Simplified) Anatomy of a Crash

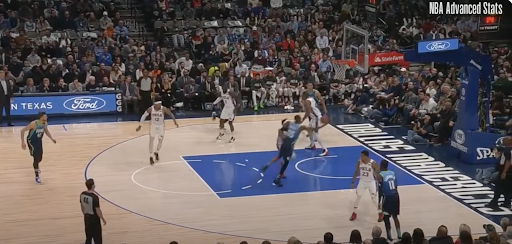

To begin, lets outline what a crash looks like along various decision points. Consider this play that develops into offensive rebound by Dorian Finney-Smith:

We can split a crash opportunity like this into at least 4 steps:

- Pre-Shot Positioning

From left to right of the ball, Finney-Smith is in the weakside corner, Powell is in the dunker spot, Kleber is on the wing, and Hardaway Jr. is on the strongside corner. As we'll delve into, this has effects on all of first shot offense, crash probability, and the chance of securing a rebound.

- The Shot

The shooter Wright attempts a driving layup in the paint in isolation against Richardson. Note that details of the shot such as degree of help drawn and location4 has a large impact on the potential rebound outcome.

- The Decision to Crash

As the shot is going up, Finney-Smith and Powell crash to the basket, while Kleber and Hardaway Jr. (as clear from the bottom image) begin to retreat. Finney-Smith takes a "backdoor" crash path to the basket from the corner while Powell is more stationary because he's being boxed out by Horford.

- 4A. (Conditional on an Offensive Rebound) 2nd Chance Offense

Finney-Smith gets an immediate putback layup out off the offensive rebound. Note that these putback opportunities are often easier than the original shot attempt because the defense is often out of position on the ensuing rebound scram. If the second chance offense has to reset this edge is no longer as prominent, particularly with the shotclock reset now being 14 seconds instead of 24 seconds.

- 4B. (Conditional on a Defensive Rebound) Transition Defense

Because this ends up in a made second chance shot, transition defense is not a factor. However, if the shot had missed, the personnel as well as some of the strategic decisions made in steps 1-3 would have had a significant effect on the transition defense. For example, one could argue that Dallas' floor balance is off, with 4 players past the free throw line extended, allowing Philly the easy possibility of leaking out in transition conditional on securing the defneisve rebound. On the other hand, all 5 Philadelphia players have also committed to being inside of their own free throw line extended, with several attempting to provide defensive rebound support, meaning there's no one to outlet to.

Space and Crash

One of the key contributors to the interaction effects between offensive rebounding and shooting efficiency is pre-shot positioning ("Step 1"). Widely scheme and personnel dependent, but positioning forwards outside the 3-point line generally improves first-shot offense (by giving the initiator more space to operate) but generally decreases offensive rebounding chances (by increasing the distance from a potential offensive rebounder to the basket; as we'll discuss later on in this section though, spacing out the opposing best defensive rebounders may provide large advantages). In 2016, Zach Lowe5 noted:

The historic drop-off goes beyond transition paranoia. Teams are playing more small ball, and asking their power forwards to shoot 3s -- slotting good rebounders 25 feet from the rim. "You're just so far away," says Kris Humphries, who barely snags offensive boards now that the Wizards have turned him into a 3-point shooter. "It's hard to run all the way in, and then run back on defense." Kevin Love, Serge Ibaka, Scola and lots of other reinvented snipers could empathize.

In 2023, we can replace "power forwards" to "forwards and centers" and "25 feet" to "30 feet" and the quote would still be accurate: teams have gone from 4-out to 5-out offenses at a much higher rate and spotting up deep behind the 3-point line has become common.

Given the (warranted) focus on space in modern offenses, I believe players who can space and crash from the 3-point line on the same possession will become very valuable. Broadly speaking, there are 2 semi-overlapping categories of offensive rebound crashes:

- a player (often a big) is already near the basket and in position to get the rebound (call it "static crashes")

- a player (often a wing) crashes in from the perimeter, often the corner 3 or sometimes the wing 3, to collect the rebound ("dynamic crashes")

Those who can credibly spot up, thus not hurting first-shot spacing, and dynamically crash, thus improving the odds of a second chance, on the same possession will likely have outsized value compared to players who force a tradeoff between spacing and offensive rebounding. The Finney-Smith clip above is one such example, as well as several from Kawhi's insane 2019 postseason run. The corner may be more feasible to crash from given the shorter distance to the basket, but crashing from above the break is also possible for special athletes like Kawhi.

Even for players without the most credible 3-point shot, crashing from the perimeter may be a way to punish defenders that are completely sagging off. Consider this play from the end of the Knicks-Cavs 2023 Game 1 that nearly broke the New York sports bar I was watching the game in:

Note that Mobley's boxout on Randle comes late because he's not closely guarding Randle on the perimeter and instead choosing to hone in on Brunson and the ball. As a result, Randle is able to crash in from above the break and secure the game-winning offensive rebound.

Drive and Kick and Crash

Another situation to gain an offensive rebounding edge while maintaining spacing and avoiding transition defense leakage is having the initiator stay near the basket in rebounding position on kickouts. Consider this play from Lauri Markkanen:

Plays like this where the creator stays near the basket to offensive rebound after driving can be very valuable because at that point they don't have a clear boxout matchup especially if they've drawn help. For a bigger creator like Markannen this can be a deadly way to generate extra putback opportunities.

Further, Markannen isn't harming first-shot spacing because he's the ones using the space created and has already created a good look at 3, and as the initiator with forward momentum he likely wouldn't have been in position to retreat back on defense anyway.

This clip also illustrates the importance of spacing for rebounding purposes. Atlanta's best defensive rebounder in Clint Capela is dragged out to contest the 3-point shot from Olynyk, leaving Markkanen with a relatively uncontested look at a tip-in.

Game State

When a team is behind especially later in a game, crashing for offensive rebounds becomes more valuable because the opportunity cost of giving up transition defense is lower. This is because the team is in a position where they need to score more points and should be risk-seeking; in the limit at the very end of the game, if they score they have a chance to win the game, if they don't they had no chance to win anyways, so giving up a transition bucket doesn't change their win probability. In addition, the opposing team is less likely to push in transition because of clock management reasons so the tradeoff is even less dangerous.

This also holds for end of quarter situations. In situations where there's not enough time for the other team to get a bucket off, it's clear that crashing aggressively has no tradeoffs to transition defense. In situations where there is enough time for the other team to get a bucket off, the other team will likely want to take the last shot so will be less likely to push in transition anyways. If they do push in transition and score too quickly, your team now has the opportunity to get another shot off.

Another area that could require further exploration is crashing more in bonus situation. It is hard to track via public data but my intuition is that the increased chance of free throws from non-shooting fouls (for example when being grabbed to prevent an offensive rebound) adds a substantial amount of value to crashing when in the bonus.

Targeting

Attacking weak point of attack defenders is a widespread strategy in the league now, but attacking rebounding mismatches may be less prioritized despite trends in the league possibly making it more valuable.

The increase of spaced 5-out offenses makes relative rebounding ability (between an offensive player and his defender) comparatively more valuable than absolute rebounding ability. The reason is that if it's less likely that there's a primary rebounder camped out in the paint due to the effects of space, an offensive player may just need to beat his primary box-out to secure a rebound; this is the basis for the "dynamic crash" category of offensive rebounding discused earlier.

This is accentuated by the strategies of modern defenses. As defenses have gotten more switch-heavy, it's more likely that after a 2-man action, a smaller guard is the primary box-out defender on a big or a larger wing. This is a mismatch that can be exploited by the offense by having the big crash. By default, teams are also trying to hide their weakest defenders on players with less on-ball offensive ability. Due to selection effects, these players are often quite athletic, else they wouldn't have made it in the league without as much on-ball ability. A natural way to attack this mismatch that's situationally more effective than attacking them with the ball is to do so on the offensive glass.

Crashing the glass against teams and players who do not push in transition at a high rate may be a component of a targeting strategy. Certain initiators known to prefer half-court offense may be better targets for crashing than those who may punish a failed crash attempt with consistent push-ahead play. On the other end of the court, against players who do not crash at a high enough rate there is likely a strategic advantage to be had having their defenders leak out early in transition when the shot goes up.

Further Questions

Thanks for getting to the end of this brain dump. Some further questions I have include:

- Which players are generating large offensive rebounding value when they do crash but don't crash at a high rate? And vice versa?

- Is this due to coaching or is it due to a lack of motor or some other individual issue?

- Is positioning and decision-making over when to crash an individual skill or something comparatively more coachable?

- To be clear it is nowhere close to completely "solved." But if you look at simple heuristics like 3PA rate, the rate of increase is slowing down, and there seems to be a general understanding that 3's, rim shots, and free throws are the most efficient shots. Getting to those shots is a different question though.↩

- https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/14505051/transition-defense-left-offensive-rebounds-cutting-room-floor↩

- https://www.thescore.com/nba/news/2536613↩

- https://squared2020.com/2019/11/18/offensive-crashing/↩

- https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/14505051/transition-defense-left-offensive-rebounds-cutting-room-floor↩